‘A ball of blinding light’: Atomic bomb survivors share their stories

A photographer pays tribute to those who suffered from the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki nearly 80 years ago.

When the U.S. dropped atomic bombs over Japan in August 1945, people were blown apart, burned, and crushed. Debris and ash descended as radioactive fallout, called black rain. The extreme heat of the explosions ignited massive fires that caused people to flee to rivers, where many drowned.

(Who is Oppenheimer? The controversial man behind the atomic bomb.)

By the end of the year, the death toll from Hiroshima and Nagasaki totaled more than 200,000. But it didn’t stop there. Many who initially survived would later succumb to radiation-induced illnesses; sometimes their children, too, suffered from related ailments. Hibakusha is the Japanese term for “atomic bomb survivors”—but given the lasting damages of radiation exposure, it’s perhaps more accurately translated as “atomic bomb sufferers.”

At the time of the Hiroshima bombing, my mother was six years old and at home, a mile away from the hypocenter (the ground directly below the explosion)—or so I thought. She never told me about her experience, and I never asked about it, as the thought of facing her vulnerability scared me. I witnessed my mother’s suffering throughout her life—from Ménière’s disease in her 30s, “blood booster” shots in her 40s, and multiple cancers in her 50s. She died at age 62. My aunt later told me that my mother might have been even closer to the hypocenter, at an elementary school where hundreds of children perished.

My grandfather died from acute radiation sickness. My grandmother died from lung cancer. My cousin, whose mother was in Hiroshima that day, developed an autoimmune disease that took her life when she was in her 50s. I was grateful to reach 50. I never thought I would survive that long.

(Discover the secrets Oppenheimer protected and the suspicions that followed him.)

Knowing the horrors of atomic bombs, many hibakusha advocate for peace. Their vision became partially realized on January 22, 2021, when the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was put into effect, but neither the U.S. nor Japan has ratified it.

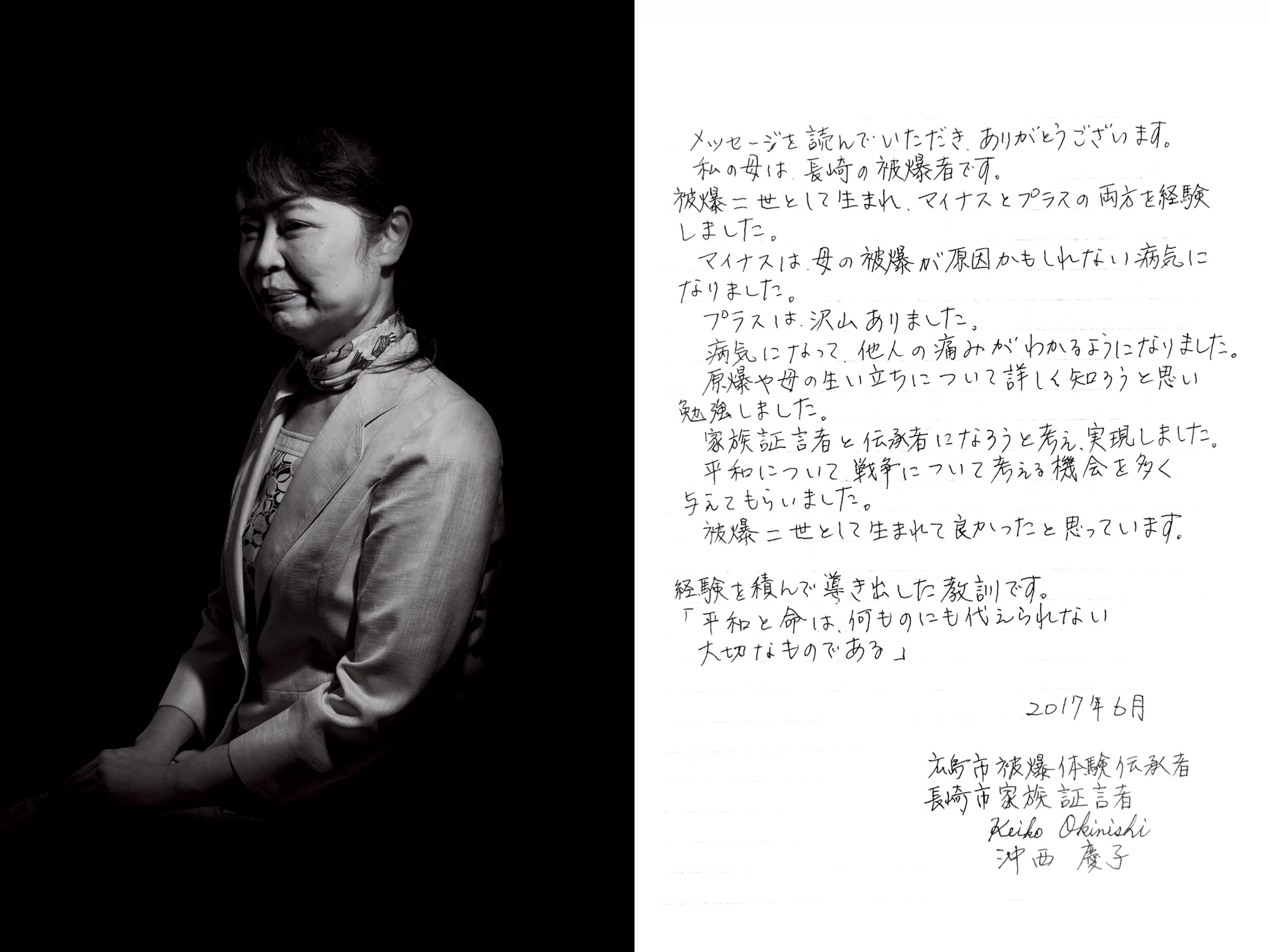

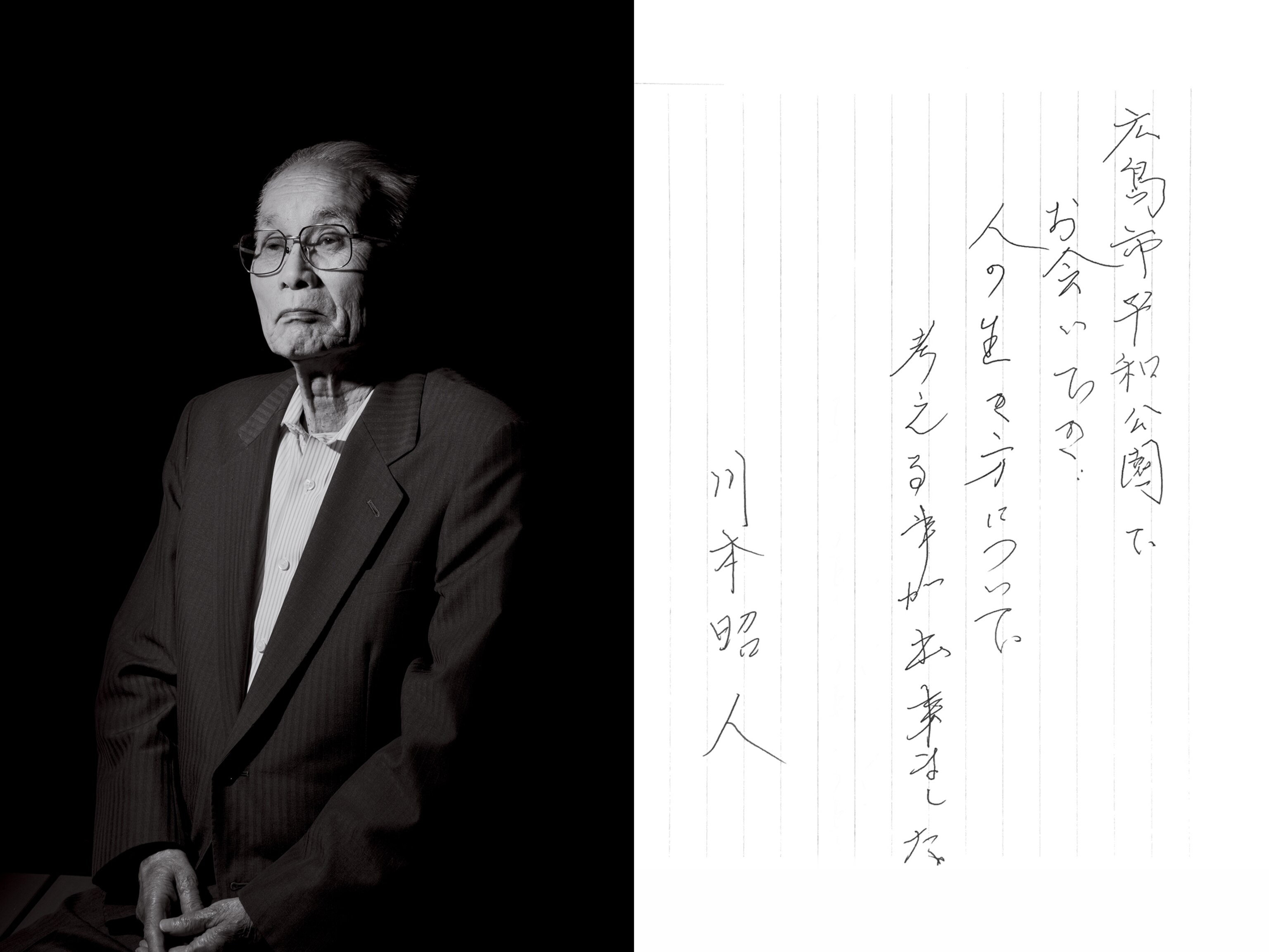

I tell the stories of hibakusha in the university courses I teach and on educational tours to Japan that I lead. Photographer Haruka Sakaguchi traveled there in 2017 to seek out hibakusha willing to share their experiences, which she preserves in her documentary project 1945.

A National Geographic Explorer, Sakaguchi pays tribute to this ever shrinking community through portraits, testimonies, and messages to future generations. I’m grateful for her work, which serves our shared goal: to ensure that this atrocity and the ongoing plight of these people aren’t forgotten.

This story appears in the September 2023 issue of National Geographic magazine.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

- Why young scientists want you to care about 'scary' speciesWhy young scientists want you to care about 'scary' species

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

Environment

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

History & Culture

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

- This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?

Science

- Why pickleball is so good for your body and your mindWhy pickleball is so good for your body and your mind

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

- What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?

- Oral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuriesOral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuries

- How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

- Science

How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

Travel

- A guide to Philadelphia, the US city stepping out of NYC's shadowA guide to Philadelphia, the US city stepping out of NYC's shadow

- How to make perfect pierogi, Poland's famous dumplingsHow to make perfect pierogi, Poland's famous dumplings

- The best long-distance Alpine hike you've never heard ofThe best long-distance Alpine hike you've never heard of

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- How to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake ComoHow to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake Como

- Going on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboardGoing on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboard